Why do depressed people make choices that are unlikely to be rewarded. And why aren’t they willing to make choices that are likely to be rewarded. In fact, why are depressed people less likely than people who are not depressed to choose to take an antidepressant, or begin psychotherapy, or follow the advice of a therapist?

A meta-analysis of many studies suggests that it is not primarily a reasoning problem. Nor is it primarily because depressed people don’t experience rewards. It is that depressed people have less of a bias towards making rewarded choices.

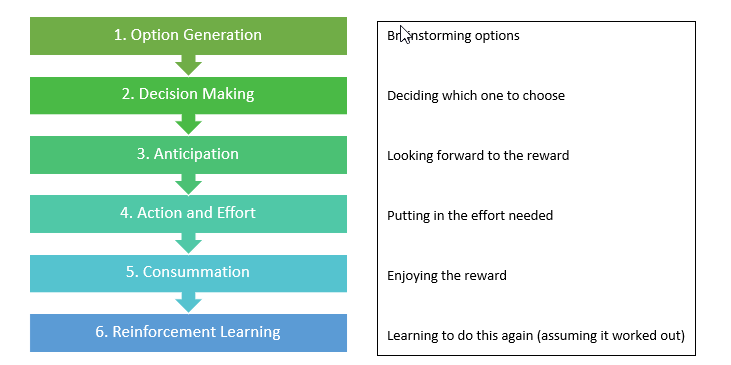

I made this chart to try to summarize the findings of the article, which can be pretty abstruse.

The first chart summarizes the decision making process

Stages of Decision Making and Action

Research has focused on 2 aspects of Decision Making –

- Option Valuation – Here you are told what the odds are of getting a reward and you have to decide whether the reward is worth the risk.

- A classic example is a study where you are told that the odds of getting a reward is 1 in a 100. The reward is 1000$. Whether or not you choose to make the effort will depend on much more than just what the reward is and how much work it takes. For example, it will depend on whether or not you have already put in a certain amount of effort and failed to get the reward (eg, in a stock market people will tend to hold on to stocks longer if they have lost money already – trying to avoid “booking” that loss – even if the odds of making the money back are pretty poor)…

- Reward Bias – How likely are you to choose one option over another if you know that the first option is more likely to be rewarded.

One aspect of Action and Effort

- Reward Response Vigor – How quickly you act to get a reward once you have done the analysis and made a decision to go for it.

And Reinforcement Learning – Do you learn the lesson of your experience the next time you have to choose…

Studies show that the biggest problem people with depression have is that a deficit in Reward Bias. In other words, depressed people tend not to make choices that they know will be rewarded as much as people without depression do (or vice versa, tend not to avoid choices that they know will not be rewarded).

One of my patients describes this as a process of “overthinking” a relatively simple decision and then, in the end, making a choice that is almost random. This he describes as a process of over-complicating decisions.

The author suggests that you may need to teach people with depression to overcome this bias in decision making (in other words, to encourage them to “go for the rewards” more of the time).

Therapists tend to assume that if they can just show the person that choice A is more likely to be rewarded than choice B they have done their job. This article suggests that they may also have to teach their client about this bias against choosing something that will be rewarded.

In a summary of the article in Journal Watch Psychiatry, Steven Dubosvky writes….

The tendency of depressed people to devalue choices and interactions that have a high likelihood of improving their lives and to repeat dysfunctional behaviors can interfere with their willingness to engage in pharmacologic and psychosocial therapies and ability to benefit from these — and can diminish their ability to maintain positive relationships. When patients understand that they have difficulty in recognizing and responding to reward, they can start to relearn reward processing, especially if significant others can help remind them when they have ignored a potentially rewarding choice. Since anhedonia is not a prominent mediator of the problem, patients may be able to experience reward once they remember how to choose it.

Steven Dubovsky

Reference

Halahakoon DC et al. Reward-processing behavior in depressed participants relative to healthy volunteers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2020 Jul 29; [e-pub]. (https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.2139)